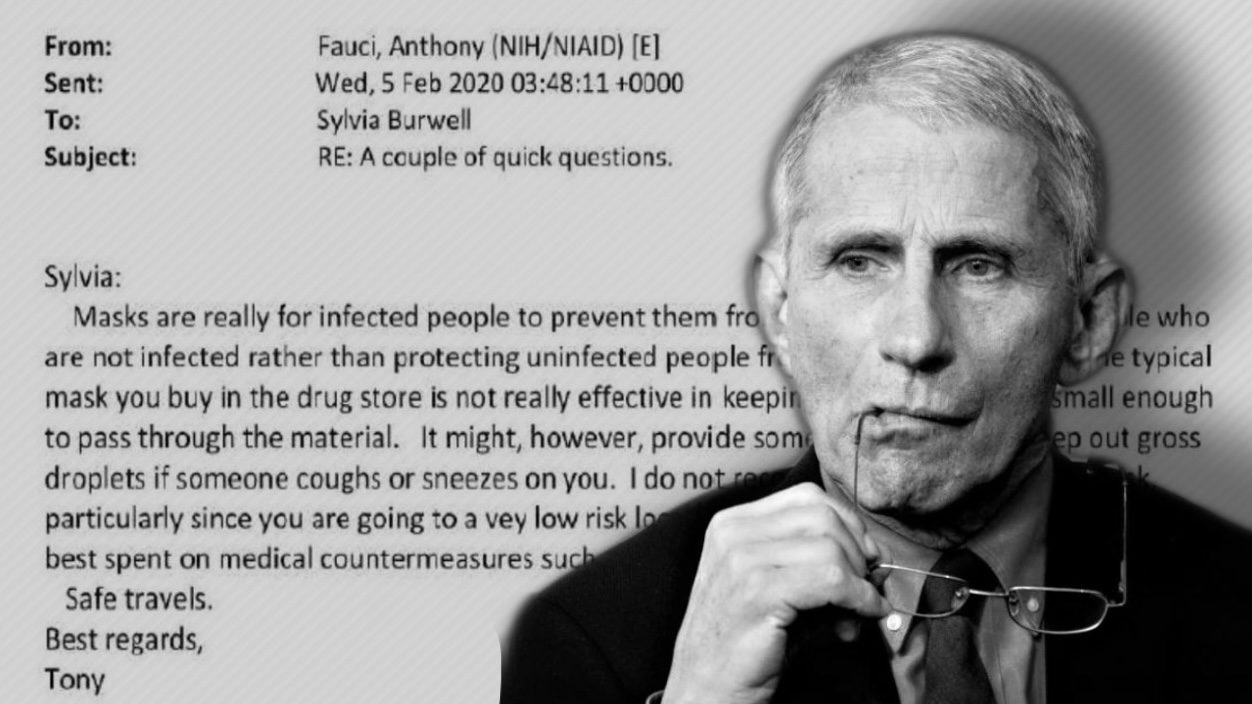

by Joe Hoft

The following report summarizes an analysis of 2020 Election

ballots scanned in Fulton County. This exclusive report uncovered

thousands of questionable ballots.

There are numerous questions related to what happened in the State

Farm Arena in Fulton County Georgia during the 2020 Election. The Arena

was used as the Fulton County ballot processing center and is where

reportedly all 148,318 absentee ballots were scanned.

Ballots processed in the Arena were expected to be authenticated

first. Voters were to be identified on voter logs and then signature

verification was to take place. The ballots were then to be separated

from their envelopes and arranged in batches of approximately 100. Each

batch was then scanned using one of the five Cannon DR-G2140 high-speed

machines [as can be observed in video from the Arena on Election

night.] The image of each ballot was simultaneously created and saved.

As a result of

a previous lawsuit,

Fulton County produced scanned absentee ballot image files which were

then made public and have been under review by various individuals and

groups.

One individual examining the data (RonC) identified something he

could not explain. The image files have timestamps that are recorded as

the ballots are being scanned. Those timestamps reveal that

the image files were created faster than the physical capacity of the

scanners used in the process. In many cases, several times faster.

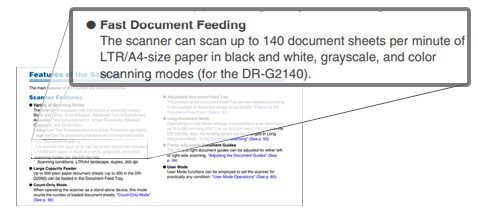

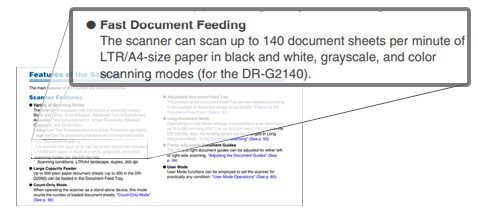

The

manual for the Cannon DR-G2140 lists the specifications on page 23:

The manual for the Cannon DR-G2140 lists the specifications on page 23:

The manual shows the machine has a maximum capability of scanning up

to 140 document sheets per minute, or roughly 2.3 pages per second.

This rate is based on scanning standard 8 ½ X 11-inch paper. The

absentee ballots are more than one and a half times this length at 18

inches long.

Using the State Farm Arena surveillance video, a group of

professionals analyzing the data measured the actual realized scan times

which averaged approximately 80 seconds per batch (under perfect

conditions with no paper jams or complications). Which equates to

approximately 1.25 ballots per second.

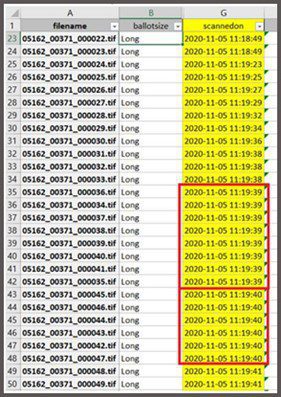

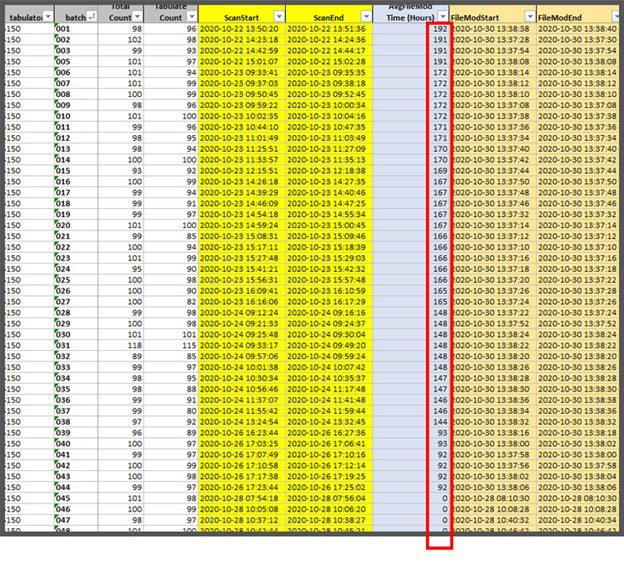

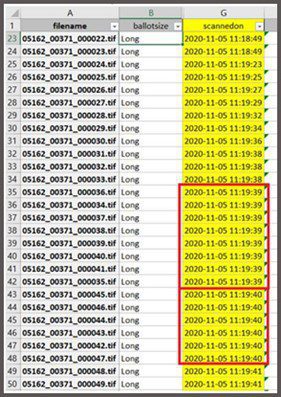

However, the image timestamps show something different. Below is a

spreadsheet of sample data that has the timestamp of each ballot image

as it was created. This information came from Fulton County and was

produced in the court case above.

Below is image data of actual ballots scanned by unit 5162 on 11-05-2020.

The timestamps in the red boxes above show 8 ballots scanned in the

same second, followed by 6 ballots in the very next second. Fourteen

ballots in 2 seconds!?!?

This shows that the ballot images were created at a speed that is physically IMPOSSIBLE.

These results are not possible.

The same scenario is replete throughout the image files and affects

thousands of ballots. These results certainly aren’t expected or

“normal”.

The group of professionals talked to several experts about these

anomalies. Given the specifics, such as the files being saved on

Ethernet-connected, high-performance network drives, and other specific

technical parameters of the arrangement,

there remains no clear and justifiable cause for these timestamps.

Even if one considers lag-time, buffering, or some type of computer

processor or network-caused “ebb and flow”, it does not explain the

impossible scan times, even when averaging all images in each batch.

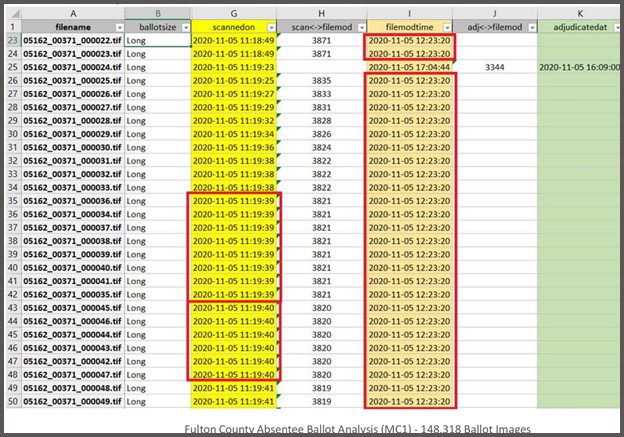

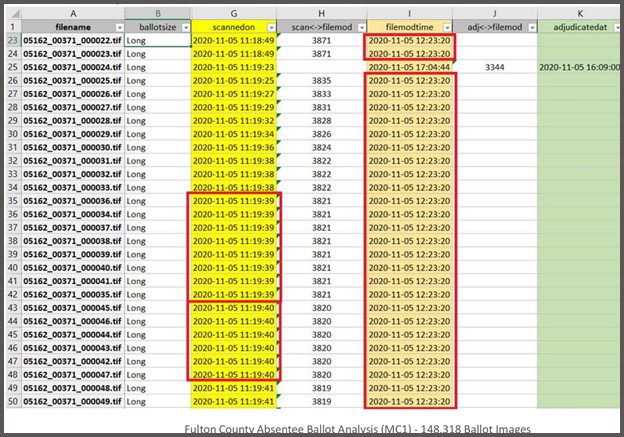

There’s more. If we expand the same dataset to include the modified file timestamps, we reveal additional problems:

The only instance in which a ballot image file should be modified is

if it has gone through the adjudication process. Adjudication is when

the machine cannot determine the voter’s selections for various reasons

and the ballot is supposed to be sent to a bi-partisan team who looks at

the markings and attempts to interpret the voter’s intent. The team

votes and if they agree, the original image is supplemented to reflect

the decision.

The modified timestamps shown above reveal that all of the files were modified.

Again, the ballot images should not be modified unless processed for

adjudication. Adjudication should only be used only in rare

circumstances. [We’re not sure of the official percent but we believe

adjudication should only occur in less than 2% of all ballots

processed.] Perhaps there is a reasonable explanation for all of these

ballots being adjudicated. Maybe this was caused by a technicality only

affecting these ballots? But the images appear to have been all modified at the same time, and within only one hour of scanning.

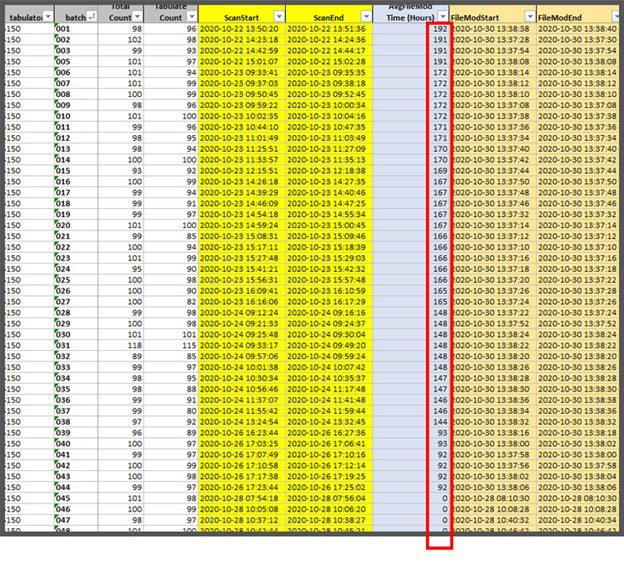

If we zoom out to the 30,000-foot level and look at all

batches from the same scanner as shown below, we see a much larger

problem. First, all of the batches have been modified as shown

on the far right. The scan times for each batch are in yellow and the

numbers shown in red are the amount of time (hours) between when the

batch was scanned and when the batch was modified.

For example, batch 001 was finished being scanned at 1:51 pm on 10/22.

That same batch was modified 192 hours later at 1:38 pm on 10/30.

The batch was scanned and then modified 8 DAYS LATER.

On scanner 5150, a total of 44 batches were modified between 3 to 8

days after being scanned. Not only is such a large window of time used

to process ballots inexplicable, but it is also unacceptable. Unfortunately, these findings show extreme variations in the process,

are widespread, and cannot be dismissed or ignored.

Important is the last 4 batches shown on the page had 0 hours between

the scan time and modification time. In fact, the last 4 batches

scanned were modified before the previous 44 batches. This removes the

possibility of some type of consistent procedure or forced process

causing the modification of all batches on the same date.

Remember, the findings above only show the anomalies associated with

one of the five machines used to scan absentee ballots, a process that

continued until November 5th. (More to come soon on the significance of the time between scanning and file modification time.)

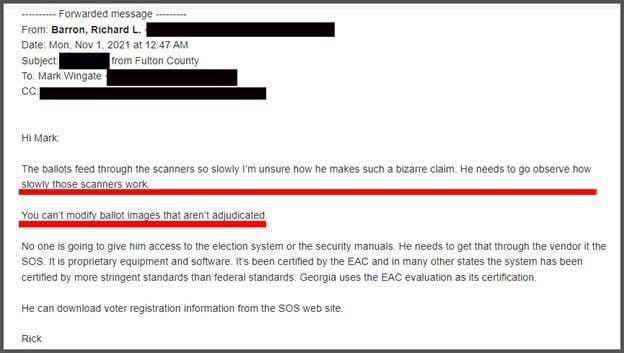

Attempting to seek understanding and answers for his findings, RonC

went to the logical government entity charged with such matters- the

Fulton County Board of Registration and Elections (BRE).

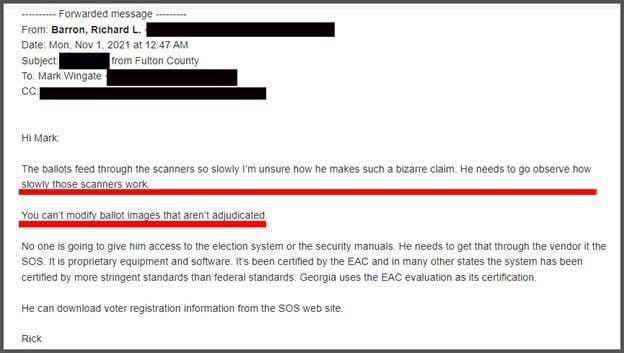

RonC summarized his findings in an email that detailed the scan speed

and image file modification issues. The BRE then sought answers from

the County Elections Director, Rick Barron. The email below shows Mr.

Barron’s response to the board:

There are 4 basic takeaways from Mr. Barron’s email.

First, it’s obvious that Mr. Barron feels the same about the

impossible scanning speed and went so far as to describe RonC’s finding

as “bizarre”. The problem is this was not simply a “claim” as

characterized by Mr. Barron, rather a factual observation of Fulton

County’s data.

Secondly, Mr. Barron directly states: “You can’t modify ballot

images that aren’t adjudicated.” Again, he affirms our understanding

and expectations.

Third, he states that the equipment is proprietary, and the security

manuals are not available. In his defense, Mr. Barron was probably

referencing the election system as a whole or in a general connotation;

however, the scanners used were Cannon consumer-off-the-shelf machines

that can be purchased through numerous retailers.

Finally, we did follow Mr. Barron’s advice to observe the scanners in

operation by watching the State Farm Arena surveillance video. He was

correct, the scanners are slow. In fact, they are so slow that the

ballot images produced by the scanner are created faster than the

machine can scan the ballots, and that truly is “bizarre”.

There is more to this story.

Kevin Moncla

“RonC” contributed to this report